Occupation

Engineer, Astronomer, Mathematician

Year Born

1231

Research Areas

Hydraulic Engineering, Astronomical Instruments

- Early Life

Guo Shoujing was born in 1231 in Xingtai, a city in the Hebei province of China. We don't know much about his parents, but his grandfather, Guo Yong, was well known for his skills in maths, reading, and water engineering. Guo likely learned a great deal from him while growing up.

At just 14 years old, Guo Shoujing built a working water clock shaped like a lotus flower. By the age of 16, he was already studying mathematics and showing signs of his talent.

During Guo's early life, northern China was in the middle of a war. The Mongols, led by Genghis Khan's family, were expanding their empire. This made it a difficult but exciting time to live, especially for someone with skills that could help rebuild and improve the country.

- Career Highlights

Guo began his career as a water engineer at the age of 20, where he fixed bridges and managed rivers in Hebei. His talents brought him to the attention of important leaders, including Kublai Khan, who was the ruler of the Mongol Empire. Guo's friend, Zhang Wenqian, introduced him to Kublai, who could see Guo's potential.

Guo worked on major water projects, such as building long canals and finding new water sources to supply the capital, including Dadu (now Beijing). His smart designs helped prevent floods and improved farming by getting water to the right places.

However, Guo was more than just an engineer; he was also a brilliant astronomer. He created tools to help with his observations. One of the tools he improved was called a gnomon. It's a very simple instrument, just a stick standing upright. By watching how long its shadow is during the day, people could learn about the Sun's movement. In summer, the shadow is shorter and in winter, it is longer. The shortest and longest shadows happened at the solstices.

To make it easier to measure, Guo added a crossbar to the top of the stick. This created a small point of light, much like a pinhole camera. The tiny spot of light cast a clear shadow on a marked scale, making it easier to see precisely when the solstices occurred and thus making observations more accurate.

Guo was one of the people tasked by Kublai Khan to make a more accurate calendar. To do this, 27 observatories were built across China to collect data. Using new tools and clever maths, including spherical trigonometry, Guo created a calendar so accurate it stayed in use for over 360 years! He worked out the length of the year almost exactly - only off by 26 seconds.

Guo was later made head of the observatory in Beijing and the Water Works Bureau. Even after Kublai Khan's death, leaders continued to seek his advice.

- Legacy

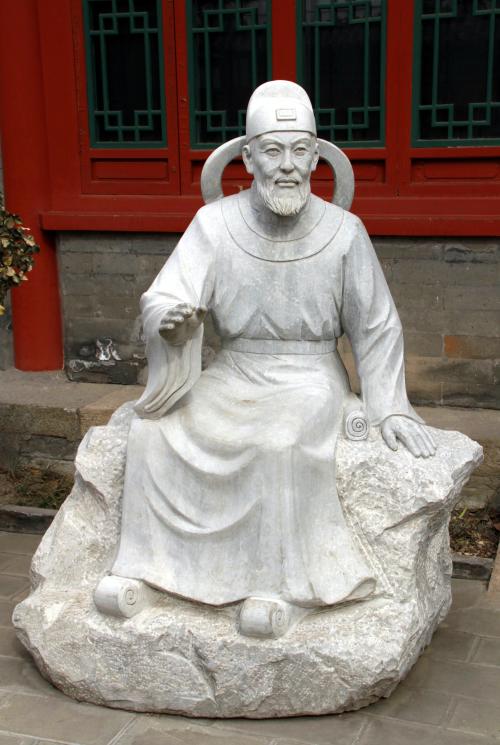

Guo Shoujing is remembered as one of China's most talented scientists and engineers. His calendar was so precise that it lasted for centuries. He showed that careful measurements and clever maths could help solve big problems, both in the sky and on the ground.

His work helped shape China's cities, farmlands, and knowledge of the stars. He also helped make science more practical by focusing on solving real-world problems rather than just theory.

Today, he is regarded as one of the most inspiring figures in the history of Chinese astronomy and engineering. Asteroid '2012 Guo Shuo-Jing' is named after him. The Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fibre Spectroscopic Telescope (LAMOST), near Beijing, is also known as the 'Guo Shoujing Telescope' in his honour.

- Other Interests

Guo wasn't only interested in the stars and rivers. He also loved solving tricky math problems. He created special equations and methods to help with his work, including clever ways to estimate distances on curved surfaces like the sky.

Even though more accurate values of pi were known at the time, Guo sometimes chose simpler ones when they gave better results in real-world situations. This showed how much he cared about usefulness, not just perfection.